You are here

Gender discrepancies in out-of-school rates

Gender discrepancies in out-of-school rates

By Joy Cheng, Intern, Education Policy and Data Center

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) alone has more than half of the world’s out-of-school children of primary age. What is the relationship between gender and schooling exclusion in the region? Are girls consistently the more vulnerable out-of-school population across different countries? Using available 2010 to 2012 household survey data in the EPDC database, this blog post compares the out-of-school rate among boys and girls of primary age in SSA countries, as well as boys and girls of different wealth quintiles and localities (urban versus rural) within a country to help answer some of these questions.

GPI for out-of-school rate

In the EPDC database, 18 SSA countries have data available from household surveys between 2010 and 2012. It is noticeable that the overall out-of-school rate for primary school-aged children[1] varies greatly among the countries, ranging from a low of 3.7% in Gabon to a high of 48.2% in Burkina Faso. It is therefore important to bear in mind that a high or low GPI for out-of-school rate may also represent a low overall out-of-school rate, as in the case of Gabon where the rate is less than 5% for each gender.

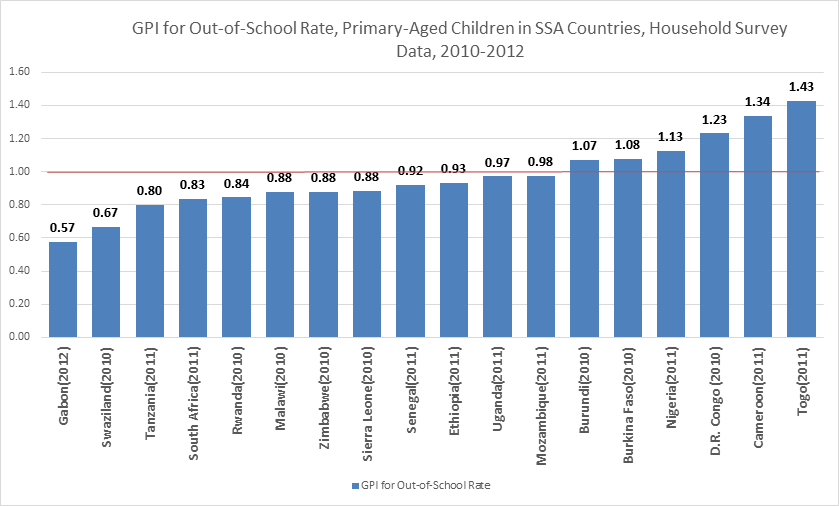

To compare the out-of-school rate between boys and girls in these countries, a Gender Parity Index (GPI) for out-of-school rate is constructed and shown in the graph below. Since GPI is calculated using the female-to-male ratio of out-of-school rate, it is noteworthy that a GPI above 1 indicates a higher out-of-school rate for girls, i.e. a disadvantage for girls, and a GPI below 1 indicates a disadvantage for boys.

According to the graph, among the 18 SSA countries with available data, 6 of them – including Burundi, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon and Togo – have a GPI above 1, which is consistent with a hypothesis that girls are more likely to be out of school than boys. However, in contrast are the 12 other countries that have a GPI below 1, meaning that boys of primary school age have a higher out-of-school rate than girls. The male disadvantage is especially pronounced in countries like Gabon, Swaziland and Tanzania, all of which have a GPI at or below 0.8.

Out of school rate by wealth and locality

For the 12 countries with a GPI lower than 1 in the above analysis, are boys consistently more disadvantaged than girls with regard to being out-of-school when factoring in other characteristics? The household survey data in the EPDC database are particularly useful for showing a rich level of subnational and between-group disparities. Tanzania is selected as a country of analysis as it has a GPI of about 0.8 for out-of-school rate. Using the 2011 household survey data, the graph below shows the out-of-school rate by gender and wealth quintiles. As can be seen, boys in almost all wealth quintiles – from the poorest and poorer to the middle and richer – consistently have greater out-of-school rates than girls in the same quintile. The only exception is the wealthiest boys, who have the lowest out-of-school rate compared with all other groups.

.png) Similar results are found in the majority of the countries with a GPI below 1. For example, in all of the 7 countries with a GPI for out-of-school rate below 0.9 (including Gabon, Swaziland, Tanzania, Rwanda, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Sierra Leone[2]), the poorest male has the highest out-of-school rate among all groups. In most cases, males in each wealth quintile have greater out-of-school rates than females in the same wealth quintile.

Similar results are found in the majority of the countries with a GPI below 1. For example, in all of the 7 countries with a GPI for out-of-school rate below 0.9 (including Gabon, Swaziland, Tanzania, Rwanda, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Sierra Leone[2]), the poorest male has the highest out-of-school rate among all groups. In most cases, males in each wealth quintile have greater out-of-school rates than females in the same wealth quintile.

Conclusion

This blog post shows that among the sub Saharan African countries analyzed, boys of primary age are more susceptible to being out of school at primary ages, than girls. Anecdotal evidence shows that in some pastoralist regions in Tanzania for example, boys are more likely to drop out of school to take care of livestock. More research needs to be conducted to discover the reasons behind the gender discrepancy. What are some other possible reasons for the male disadvantage in out-of-school rates in these countries? Is it possible that household incentive schemes such as cash transfer programs aimed at promoting girls enrolment in primary school have resulted in a reversed gender gap at the expense of boys? Please comment below to share your perspective.

Add new comment