You are here

EPDC Spotlight on Morocco

EPDC Spotlight on Morocco

Each week, the EPDC Data Points blog will highlight a different country and the resources we offer, such as data, country profiles, research or other tools that users have available to them through the website. Our fourth post in the series highlights Morocco, and Kemi Oyewole once again provides an overview of education in the country and the data resources we have that are publicly available.

Morocco is a North African country with a population of about 33 million people. In an August 2013 speech, King Mohammed VI of Morocco shared that “the state of education [in Morocco] is worse now than it was twenty years ago” and should be the nation’s top priority. His criticism stems from a lack of efficiency in education system evidenced by: the lack of alignment between curricula and job market, changing languages of academic instruction, and the pressure Moroccan families face to send children to private schools to obtain a quality education. King Mohammed VI’s charge to transform Moroccan education points to his belief that educational reform is the key to economic and social progress.

The Moroccan school system begins at age 6 when students enter six years of primary school. This is followed by three years of lower secondary school and three years of upper secondary school. Primary and lower secondary school are referred to as basic education, which is free and compulsory.

Learning Outcomes

At the conclusion of primary school, students sit for the Certificat des Études Primaires. Likewise, students sit for the brevet D’Enseignement Collégial to complete lower secondary school and the Baccalauréat d’Enseignement Général to complete upper secondary school. Then students have the opportunity to enter institutions of higher and vocational education.

Additionally, the Moroccan government administers the Programme National d'Evaluation des Acquis (PNEA) as a national large scale assessment for students in the fourth, sixth, eighth, and ninth grades. The PNEA assesses Arabic, French, mathematics, and science, mapping to three of the seven domains deemed important for learning by the Brookings Institute and UNESCO Institute of Statistics’ Learning Metrics Task Force.

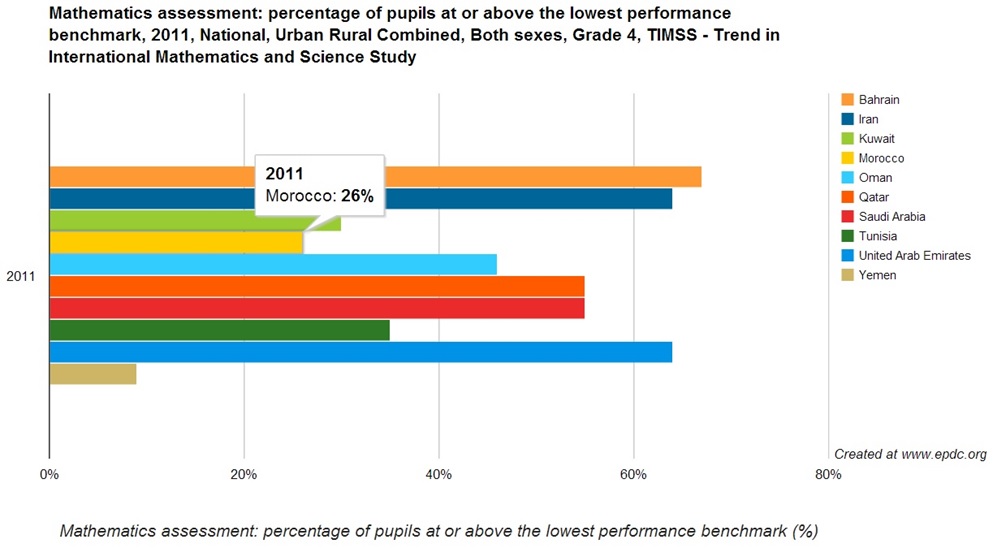

Figure 1: Percentage of Grade 4 Pupils reaching the Lowest Performance Benchmark in Mathematics

The Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA), Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) are internationally comparable assessments that have evaluated Moroccan students. From these cross country comparisons, it is evident that Morocco falls behind many countries in the Middle East and North Africa in the percentage of students reaching learning benchmarks (Figure 1). Such results illustrate the urgency with which Morocco must increase educational quality in order to remain regionally competitive.

Education Data: A Snapshot

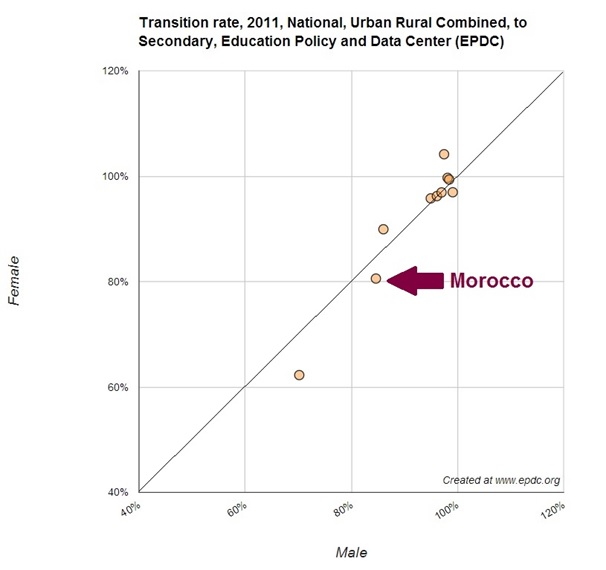

The 2011 transition rate to secondary school in Morocco was 80.6 percent for females and 84.6 percent for males (Figure 2).[i] By 2025, EPDC Projections estimate that the secondary school transition rate in Morocco will be 93 percent for females and 95 percent for males. This implies that in a decade the vast majority of students who have completed primary school will be entering secondary school, regardless of gender. Such convergence of educational access across genders suggests a promising increase in the opportunities available to women and girls in Morocco. The EPDC website hosts a wealth of data on education in Morocco including: demographics, educational expenditure, literacy, and gender parity. More detailed descriptions of Moroccan education can be found in its Education Profiles.

Figure 2: Secondary School Transition Rates for Females and Males in the Middle East and North Africa[ii]

Issues of Educational Quality and Equity

In 2013, the World Bank extended a 100 million dollar loan to Morocco in order to continue the nation’s educational development. These funds are to be directed towards initiatives intended to improve educational quality as enrollment in primary education approaches universality. Such initiatives include regional teacher training, enhanced efficiency of education though decentralization, and school boarding scholarships. The second iteration of Education Development Policy Loan builds upon the first, which focused on encouraging poor rural families to send their children to school.

A First Grade Classroom near Meknes which is part of a Targeted Cash Transfer Program (photography by Arne Hoel, The World Bank)

There is quite a disparity in school completion by wealth quintiles in Morocco. In fact, urban rich women have a completion rate seven times higher than urban poor women. This further illustrates the need for poor students to not only enroll in school, but to complete their education and to experience substantive learning. It also suggests that wealth plays a large role in the educational experience of Moroccans.

Further evidence of the role wealth plays in Moroccan education has emerged through controversy regarding the increased privatization of schools in Morocco. The Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights organized a coalition which submitted a report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. The coalition’s report found that, “increasing privatization in education in Morocco without strong government regulation is discriminatory, likely to exacerbate inequality, and if not properly dealt with in an expeditious manner would rise to a violation of Morocco’s obligations under international human rights law.” This raises awareness of the need for Moroccan public education to reach all students, despite their socioeconomic standing.

In regards to academic instruction in Morocco, some advocates are suggesting a change in language used for early childhood instruction to promote learning at the primary level. Darija is the colloquial form of Arabic spoken in most Moroccan homes. However, Modern Standard Arabic, or fus’ha, is the Moroccan language of instruction. Advocates for teaching darija site the recommendation of UNESCO that mother tounges be used in early childhood education. However, opponents of the change believe movement away from fus’ha will isolate Morocco from the rest of the Arab and Islamic communities. Resolution of this language learning debate will allow for the development of materials needed to provide quality reading instruction and bring Moroccan students on par with their peers across the Middle East and North Africa.

EPDC Resources

Among other sources, unique EPDC data collections for Morocco include data from the Bureau of Statistics (2010, 2011), USAID Demographic and Health Survey (2004), the Early Grade Reading Assessment (2011), the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (2006, 2011), the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (2003, 2007, 2011) and other indicators derived from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. The EPDC website offers users the opportunity to create graphs, charts, and other visualizations of data with an easy-to-use tool.

[i] Transition rates are calculated as: the number of pupils admitted to the first grade of higher level education in a given year, expressed as a percentage of the number of pupils enrolled in the first grade of the lower level of education in the previous year.

[ii] Countries graphed include: Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Iran, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.

Add new comment