You are here

EPDC research on equity published in Journal on Education in Emergencies

.jpg)

Celeste Carano, Research Intern

Can countries build social cohesion through investments that aim to boost educational equity? Particularly for conflict and post-conflict societies, educational opportunity is viewed as a key pathway to counter past discriminatory policies. EPDC’s recently published paper, “The Limits of Redistributive School Finance Policy in South Africa” in the Journal on Education in Emergencies, delves more deeply into this question with a case study on South Africa. The paper, which was based on EPDC researchers Carina Omoeva and Rachel Hatch's research for UNICEF and Learning for Peace on investing in equity and peacebuilding, argued that while South Africa’s current policy can be viewed as pro-poor, it is having little impact on social cohesion or equity.

Over the past two decades, South Africa has rolled out a progressive educational funding policy aiming to counteract the legacies of apartheid in the education system. One of these policies aimed to alleviate cost as a barrier to access to education by eliminating school fees for families attending schools in low-income communities. The first phase of these school fee reforms waived fees for two out of the five poorest categories of schools and the most recent 2010 reforms eliminated school fees for the next lowest-income school level. Schools in South Africa are broken into quintiles by wealth of the surrounding community, meaning this policy covers the three lowest quintile schools currently (Q1, 2 and 3). EPDC’s research assesses whether this policy has led to increased educational equity and improved social cohesion. The research used a mixed methods approach that included qualitative fieldwork in two provinces as well as quantitative analyses (drawing on data from the South Africa Statistics office) of household expenditures on school fees, perceptions on the school environment before and after the no-fee policy, and teacher-student ratios.

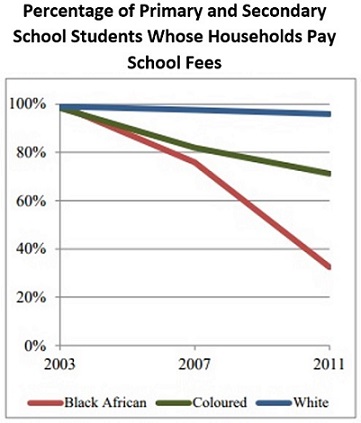

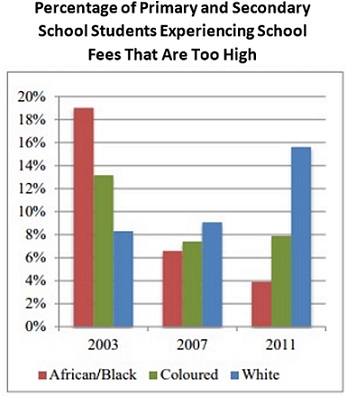

The findings show that black South Africans perceive their families to be better off now. After the no-fee policy change, only 32% of black South Africans reported paying fees. In contrast, white South Africans have seen fees rise. 95% of white South Africans report paying fees, and 15% view school fees as a burden. Data also shows that the no-fee policy has helped secure a minimum resource base for all schools and improved teacher availability. EPDC’s researchers characterized the policy as pro-poor for these reasons – but found that it does not seem to be impacting equity. Student-teacher ratios remain lower in higher-income quintile schools for example – 29:1 in Q5 schools versus 29-32 in Q1-Q3 schools - because fee collecting schools can hire more teachers with their additional resources.

The study pointed to limitations in the current policy that have limited its reach and impact. Most notably, to encourage movement across school categories, low income children can apply for exemptions to school fees to attend a higher ranked quintile school. This could, in principle, help counter unequal access to high quality and well-resourced schools resulting from housing segregation, another apartheid legacy. But, in practice, the fee requirement can be used to exclude children based on wealth, class, race, or language. Testifying to this, since the 2010 policy was implemented, the top quintile schools have seen their proportion of white students increase, while lower quintile schools continue to serve primarily black children. The percentage of white students attending Q5 schools reached 87% by 2013, an increase of 5 percentage points since before the introduction of the policy. In short, while government education investments have been geared towards low income and marginalized children, parental spending by high income (typically white) families outpaced it.

In addition, not all high quintile schools are well resourced. Schools are classified into quintiles based on community characteristics. As a result, some schools can be in a wealthy area, but also have poorer children living in adjacent neighborhoods – children whose families cannot contribute via school fees, and whose school nonetheless receives lower government funding because it is categorized as an upper quintile school despite serving a high need student population. The needs of these schools are unmet under the existing policy. Because of these continued inequalities, while black families expressed satisfaction with the reduced cost of education, they expressed dissatisfaction with the continued obstacles to enrollment in the best schools for their children.

While it would be easy to dismiss the South African government’s policies as ineffective, EPDC researchers ultimately argue that South Africa’s case shows just how challenging it is to create policies that can undo a long history of discrimination. The South African Department of Basic Education has attempted to invest in policy research and evaluations of its programs and repeatedly shifted its approach in the past decades, including this most recent change to school fees. Governments attempting similar changes should understand that building equity in and through education requires flexibility and persistence.

Add new comment