You are here

Economic inequality and schooling in Colombia

Economic inequality and schooling in Colombia

The following is based on the research interests of Yui Hosokawa, M.A. in Economics (in process), Kobe University, who was a visiting research intern with EPDC in December, 2013

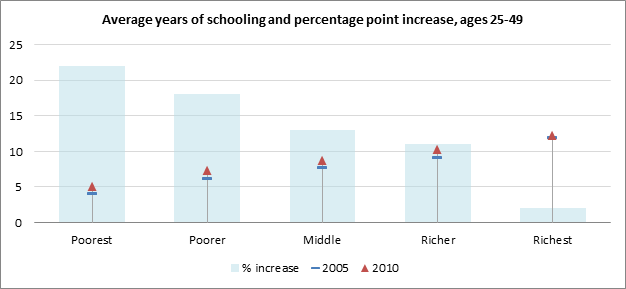

Colombia has long had one of the highest rates of economic inequality in Latin America. Although the Colombian GINI index in recent years has decreased, it was still 55.9 percent in 2010 and among the highest in Latin America. How do factors such as educational attainment and school attendance vary among Colombians in different economic quintiles? How has the gap changed in recent years? Data shown here are from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) in 2005 and 2010, extracted by the Education Policy and Data Center (EPDC), FHI 360. Economic data are captured at the household level and based on asset ownership, and divide respondents into poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest quintiles. As the chart shows, average years of schooling increased in every household wealth quintile between 2005 and 2010. However, we also see that the average years of schooling vary by quintile for both years. In the poorest group, the average years of schooling is roughly 5 years whereas the average years of schooling for those in the richest quintile is roughly 12 years. Nevertheless, the largest increases in average years of schooling between the two years are for the poorer segments of the population, suggesting that Colombians from lower household wealth quintiles are acquiring greater access to education opportunities.

Colombia has long had one of the highest rates of economic inequality in Latin America. Although the Colombian GINI index in recent years has decreased, it was still 55.9 percent in 2010 and among the highest in Latin America. How do factors such as educational attainment and school attendance vary among Colombians in different economic quintiles? How has the gap changed in recent years? Data shown here are from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) in 2005 and 2010, extracted by the Education Policy and Data Center (EPDC), FHI 360. Economic data are captured at the household level and based on asset ownership, and divide respondents into poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest quintiles. As the chart shows, average years of schooling increased in every household wealth quintile between 2005 and 2010. However, we also see that the average years of schooling vary by quintile for both years. In the poorest group, the average years of schooling is roughly 5 years whereas the average years of schooling for those in the richest quintile is roughly 12 years. Nevertheless, the largest increases in average years of schooling between the two years are for the poorer segments of the population, suggesting that Colombians from lower household wealth quintiles are acquiring greater access to education opportunities.

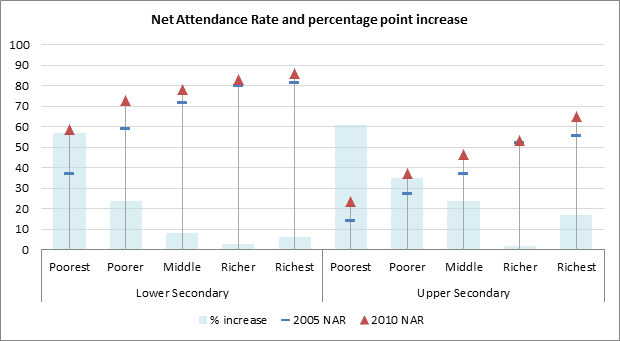

Another way of looking at the relationship between schooling and household wealth is for those currently attending school. The above chart shows the net attendance rate by wealth quintile, in 2005 and 2010, along with the % increase between the two years. There are clear differences in secondary attendance rates when stratified by wealth quintile. The net attendance rate is lower for poorer segments of the population regardless of level of secondary schooling, and increases with wealth. However the differences between 2005 and 2010 show that, similar to average years of schooling, the greatest increases in attendance rates are for the poorest, poorer and middle-income households. The richer and richest quintiles saw the smallest increases between the two years.

Another way of looking at the relationship between schooling and household wealth is for those currently attending school. The above chart shows the net attendance rate by wealth quintile, in 2005 and 2010, along with the % increase between the two years. There are clear differences in secondary attendance rates when stratified by wealth quintile. The net attendance rate is lower for poorer segments of the population regardless of level of secondary schooling, and increases with wealth. However the differences between 2005 and 2010 show that, similar to average years of schooling, the greatest increases in attendance rates are for the poorest, poorer and middle-income households. The richer and richest quintiles saw the smallest increases between the two years.

Trends shown in the data have implications for universal schooling access, as the Colombian school system includes lower secondary in its basic education sequence. A movement towards providing free and universal education has been signaled in a number of law and policy changes in recent years - in 2010 the Colombian Constitutional Court declared that all primary schools must cease charging fees, and a 2012 presidential decree extended this to the secondary level. While such moves signal a commitment by the Colombian government to ensure increased educational access across the country, it is important that benefits are felt by all segments of the population, regardless of wealth or other factors. Alternative schooling methods can provide one way for policymakers to continue extending educational opportunities to children from all socioeconomic backgrounds. FHI 360 has done extensive work with alternative and non-formal schooling in Colombia and in other Latin American countries, demonstrating the importance of factors such as community participation and strong teacher support to children’s schooling, learning outcomes and cost-effectiveness. In addition to large-scale policy initiatives such as cash transfer programs, governments are considering such alternative schooling models as a way to extend opportunities for schooling and quality education to all segments of the population.

The data show that there remain persistent economic disparities in schooling access and attainment in Colombia, particularly beyond the primary level. However, there were notable increases in access and attainment among poorer segments of the population between 2005 and 2010, indicating Colombian students from all economic backgrounds are receiving increased education opportunities.

-

Does the increase in educational attainment and access seen based on the DHS data necessarily indicate an increase in educational opportunity for poorer segments of the population? How can increases in access result in better education quality, job market prospects and overall improvement in livelihood for poor Colombians?

-

Are levels of economic inequality adequately captured in composite wealth score indices such as the one used by DHS? What other individual or household factors could be incorporated to provide a more comprehensive picture of economic inequality in a given country?

Add new comment