You are here

The Nickels and Dimes of Education for All: Excerpts from EPDC's Latest Research

This post present excerpts from our latest research, The Nickels and Dimes of Education for All: The expansion of Primary Education in Sub-Saharan Africa, by Carina Omoeva and Ania Chaluda.

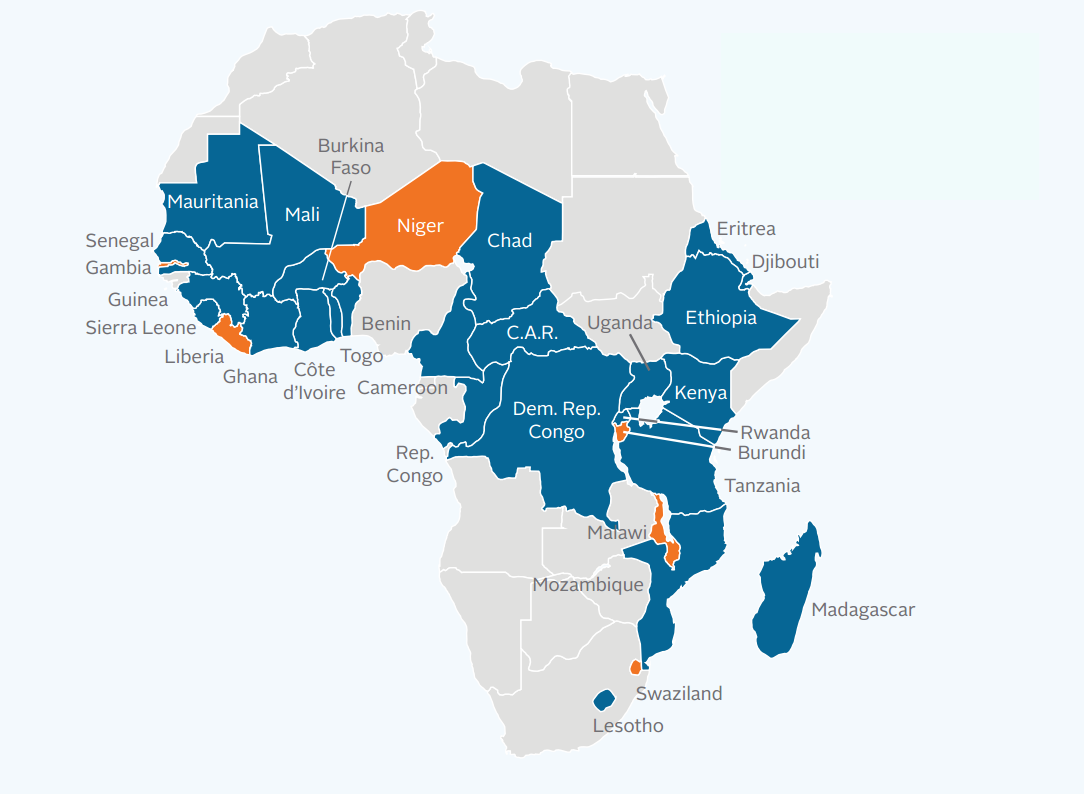

Figure 1 - Countries expected to run a budget surplus (blue) and deficit (orange) between 2015-2025 at current levels of primary per-pupil expenditure

Introduction

With the benchmark year of 2015 just around the corner, the discussion around Education for All (EFA) goals once again turns to the issue of finance. The lack of funding — and specifically the inability of donors to come through on pledges made in the year 2000 — has been cited as one of the principal reasons the world has fallen short of accomplishing the ambitious Education for All agenda by 2015. We argue that this pessimistic view of the need for ever increasing donor flows to address education deficits is wrong. EFA can be achieved faster and with a lower donor cost with two key changes to international policy. First, a focused effort to mobilize resources in the developing countries themselves is needed, both to generate needed funds and to promote an environment of shared accountability for financing education. Second, these increased domestic resources need to be focused on the most important constraints to school completion, in light of the significant achievements of EFA, as the critical issue in most countries is no longer barriers to entry, but rather repetition and dropout. International assistance should be present to ensure that effective technical solutions are available and continuous capacity building takes place to help governments harness domestic finance and direct it towards quality improvement. In all likelihood, however, change will not depend on increased aid nor will it happen quickly — it will rely on the commitment of national governments and the strength of their local economies.

Expansive growth

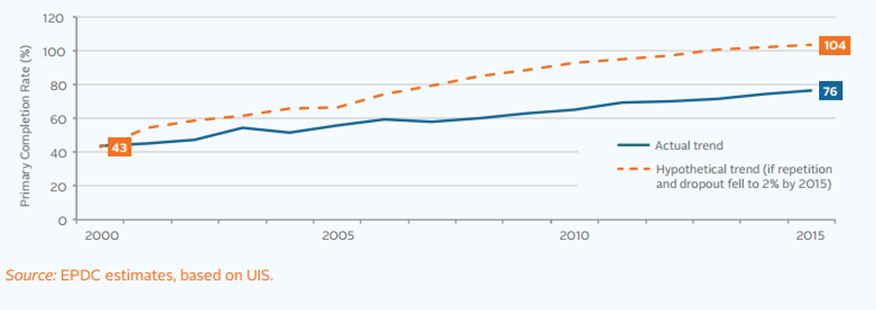

For most countries in the Global South, Education for All is largely not a challenge of initial access, but rather a struggle of keeping children in school and sustaining low repetition rates. In other words, roughly half of the students that enter the first grade of primary school in Sub-Saharan Africa find themselves repeating grades they should have completed, or dropping out of school altogether before they have a chance to reach the end of primary. To visualize the impact of retention on progress in Education for All to date, we simulated a steady decline of repetition and dropout rates between 2000 and 2015 from their actual level to no higher than 2%for a group of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and calculated the resulting average primary completion rate. The results are shown in figure 1, based on actual primary completion data for 2000–2012 and projections for 2013–2015 which are set against the EPDC hypothetical “quality improvement” trend, plotted by the dotted orange line. The difference between what “could have been” and what “was” is striking: if countries had been able to steadily advance towards higher retention every year since the year 2000, bringing grade-to-grade promotion rates to 98% by 2015, primary completion in most countries would have reached near-universal levels during this time.

Figure 2 - Actual and hypothetical primary completion rates for Sub Saharan Africa

Education finance trends

Figure 3 - Projected GDP growth 2014-2018, constant prices, IMF Economic Outlook

_11_7.png) The expansion of education systems is well reflected in increasing domestic education budget allocations. While these trends indicate progress in greater school participation and higher quality outcomes, the current levels of spending in primary school are still largely inadequate for creating a quality learning environment, particularly whendistributed across a growing population of students. Our analysis in the paper illustrates the double challenge of still-weak economic foundations in the region coupled with high demand for primary education. Thus far, education budgets have been growing steadily since Dakar and, therefore, there is reason to believe that continued growth will create greater opportunities to make headway towards universal school participation. If these economies continue their upward climb and this trend is sustained through 2025, substantially more domestic resources will be available for much-needed investments in the education sector, and efforts to expand school participation and improve quality can become less dependent on donor assistance. In order to estimate the potential that domestic resources would support this gradual expansion of the education system in the near future, we must estimate the projected cost of school participation for a growing number of students, and subtract it from the projected primary education budget. To calculate the projected costs, we use the most recent data on government expenditure per primary student in US dollars as a basic unit and, after adjusting for inflation, multiply it by the number of students projected to enroll in the system each year. The total amount generated for primary education due to economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to be about 120 billion in constant 2014 US dollars between 2015 and 2025, assuming that countries continue to devote at least 2% of GDP to primary education.

The expansion of education systems is well reflected in increasing domestic education budget allocations. While these trends indicate progress in greater school participation and higher quality outcomes, the current levels of spending in primary school are still largely inadequate for creating a quality learning environment, particularly whendistributed across a growing population of students. Our analysis in the paper illustrates the double challenge of still-weak economic foundations in the region coupled with high demand for primary education. Thus far, education budgets have been growing steadily since Dakar and, therefore, there is reason to believe that continued growth will create greater opportunities to make headway towards universal school participation. If these economies continue their upward climb and this trend is sustained through 2025, substantially more domestic resources will be available for much-needed investments in the education sector, and efforts to expand school participation and improve quality can become less dependent on donor assistance. In order to estimate the potential that domestic resources would support this gradual expansion of the education system in the near future, we must estimate the projected cost of school participation for a growing number of students, and subtract it from the projected primary education budget. To calculate the projected costs, we use the most recent data on government expenditure per primary student in US dollars as a basic unit and, after adjusting for inflation, multiply it by the number of students projected to enroll in the system each year. The total amount generated for primary education due to economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to be about 120 billion in constant 2014 US dollars between 2015 and 2025, assuming that countries continue to devote at least 2% of GDP to primary education.

Figure 4 - Key assumptions in our cost projections

_11_7.png)

The disparity between what is allocated to primary education and what could be allocated becomes evident with the example of Cameroon, where economic growth rates for the next five years are projected to average around 5% annually. At this time, about 1% of the country’s GDP is allocated to primary education. Government spending per primary student is average by regional standards, at about US$77 per year, which, adjusted for inflation, will equal approximately US$106 by 2025. As figure 4 shows, at this modest resource allocation level, which is represented by the blue area on the graph, Cameroon can accommodate growing enrollment. It is evident, however, that there is untapped potential to increase per pupil spending in the country’s economy if current levels of allocation to primary education are maintained given economic growth (this scenario is marked in light orange), and even greater possibilities may well emerge over the next decade if a greater percentage of GDP is devoted to education (marked in dark orange). It is therefore a matter of capturing this potential and directing it to meet the needs of the country’s education system.

Figure 5 - Actual and potential per pupil budget allocations for primary, Cameroon

_11_7.png)

Conclusion

While it is true that universal access and primary completion will not be accomplished by 2015, there is reason to believe that these objectives can become a reality in the medium term, if current economic trends continue. The time frame and the pace in reaching EFA goals will differ across countries, and one set of benchmarks may not fit all countries in the same way. However, as our analysis of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa showed, the task of most education systems faced with low primary completion is not to enroll more new students — it is to retain those already enrolled and improve the quality of their learning outcomes. Investment in quality, in turn, will reduce wastage of resources resulting from grade repetition and early dropout, thereby creating a virtuous circle where funds previously spent on children repeating grades would be directed towards teacher training or strengthening management systems to improve the learning experience of students newly entering primary school. In this changing context, donor aid becomes less the answer to the Education for All challenge, and more an enabling factor, with international technical assistance focusing on helping governments develop and implement solutions that address the barriers to retention and the root causes of poor learning outcomes.

For more detail, read our latest publication, The Nickels and Dimes of Education for All: The expansion of primary education in Sub-Saharan Africa

Add new comment