You are here

EPDC Spotlight on Afghanistan

.jpg)

This is the latest post in our Country Spotlight series, where we highlight a different country and the resources we offer, such as data, country profiles, research or other tools that users have available to them through the website. In this post EPDC's Charles Gale and Maxine Wang highlight the data resources we have for Afghanistan.

Afghanistan is a landlocked country located in Central/South Asia which was classified as a low-income country by the World Bank in 2014. While having diversity of languages and ethnic groups, Islam is the dominant religion in Afghanistan. Over 99% of the Afghan population is Muslim and approximately 80–85% are from the Sunni branch. Afghanistan has a 6-3-3 formal education structure. As detailed on EPDC’s Afghanistan country page, Primary school has an official entry age of seven and a duration of six grades. Secondary school is divided into two cycles: lower secondary consists of grades 7 - 9, and upper secondary consists of grades 10 - 12. According to Afghan Central Statistics Office, there were 121,593 primary schools, 3,853 lower secondary schools and 3,603 upper secondary schools in Afghanistan in 2011.

Education Data

EPDC’s National Education Profile for Afghanistan indicates that Afghanistan has a lower youth literacy rate compared with other low income countries. In Afghanistan, the literacy rate is 47% among population ages 15-24, which is lower than the average youth literacy rate in the low-income countries cohort. What compounds the challenge for education in Afghanistan is that a huge disparity exists between males and females. EPDC’s extraction from MICS shows that in 2011, the literacy rate of youth aged 15-24 was 61.9% for male and only 29.9% for female, suggesting that young men are twice as likely to be literate compared to young females. Additionally, fewer than 2 in ten women age 15-49 are literate, meaning adult women are much less likely to be able to read and write.

Educational Inequality

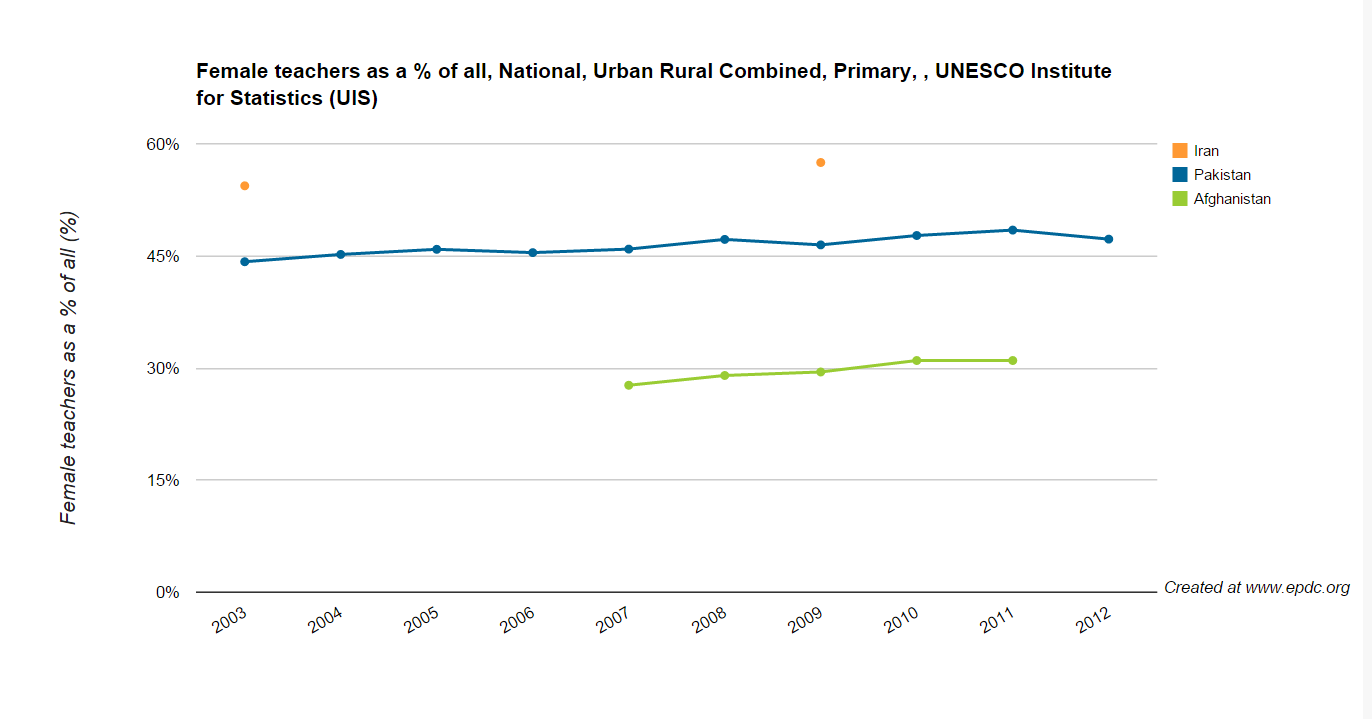

After the fall of Taliban regime in 2001, large numbers of refugees have returned to the country and the formal schooling system has been reconstructed, which allows many children, especially girls, to regain access to education. Given the fact that girls were officially denied access to school under the Taliban regime, great progress has been made in terms of universal primary education. In a case study of Afghanistan conducted jointly by USAID and FHI360 in 2004, 1.3 million girls were registered in public primary school, indicating that a functioning schooling sector gradually absorbs females back into the education system. However, despite impressive improvement in a short time, there were still 60 percent of girls of school age out of school in 2004. According to the same study, safety concern for girls was the main reason standing in the way of female universal education, causing parents to keep girls at home. For example, the distance from home to school can be a significant barrier to education. Whereas most parents allow their sons to walk or use public transportation, daughters who live more than a very short distance from the school building are rarely allowed to attend. In addition, a school system dominated by male teachers may be a concern for girls’ parents. From 2007 to 2011, female teachers only accounted for 30 percent of all teachers in primary school (Figure 1). The small percentage of female teachers who can serve as role models may make it less likely for parents to send their daughters to school.

Figure 1 female teachers as percentage of all in Afghanistan

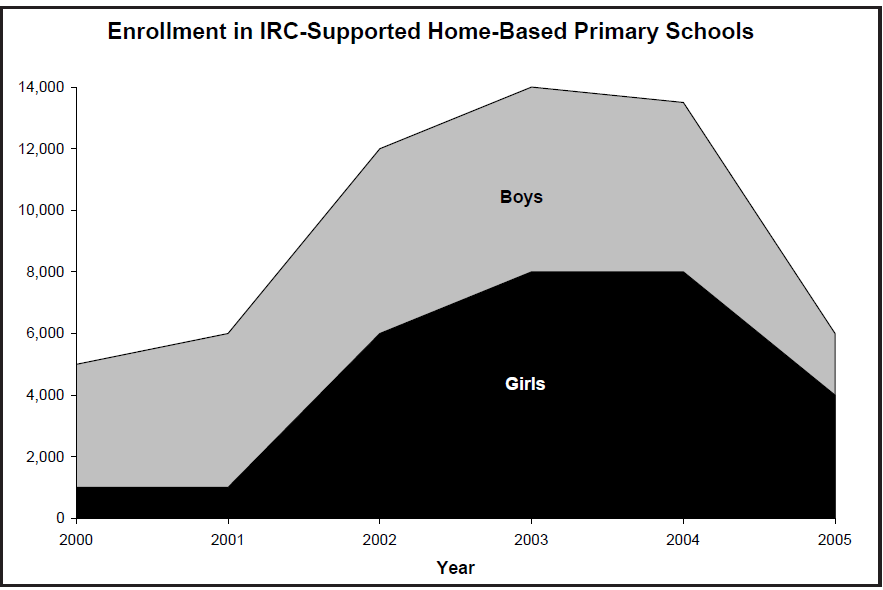

However, despite geographical obstacles and cultural issues, access to education for females in post-conflict Afghanistan can be addressed by collective efforts from the public sector in partnership with NGOs. The home-based schooling (HBS) implemented by the International Rescue Committee (IRC), as detailed in an EQUIP2 policy brief, has proven to be an effective approach to reach the marginalized in Afghanistan at a time when formal schooling system was unable to accommodate all students during the post-conflict period. HBS aims to create a female-friendly education program. In HBS, the community education committee nominates trusted local teachers, and women are particularly encouraged to become involved in teaching. By creating a convenient and safe learning environment for girls, HBS successfully attracted girls from more conservative parents. HBS absorbed a large number of girls to receive primary education through the alternative learning system. For example in 2003, the HBS program enrolled 14,000 students, nearly 60 percent of whom were girls (figure 2). The success of the HBS reflects on differences of literacy rates across age cohorts. In 2008, females aged 15-19, the generation benefiting from HBS, were nearly four times as likely to be literate than females age 25-29 (figure 3).

Figure 2 Enrollment in the HBS program

Figure 3 Female literacy rate by age cohort

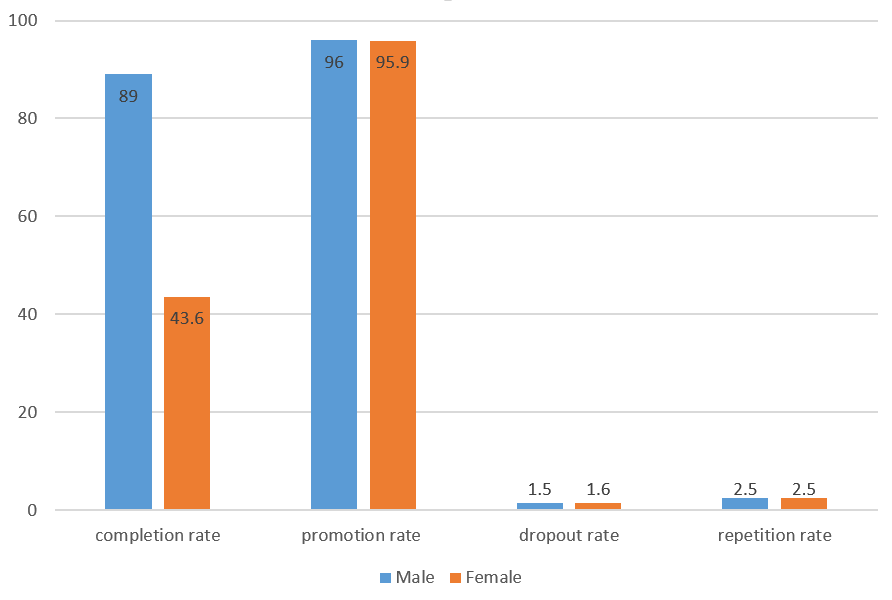

While a huge gap in access to education exists in Afghanistan, it is noticeable that girls in school were not at a disadvantage in terms of academic performance. Extracted from MICS dataset, figure 4 indicates that a larger proportion of male students complete primary education than females. However, when looking at those who were already in school, there was no gender disparity in the promotion rate, drop-out or repetition rates, suggesting that gender inequality in completing primary school is a relatively large problem. Additionally, the message implies that with equitable resource distribution for both genders, females are competitive with males in educational achievement. Therefore, for the Afghan government, it is urgent to craft female-specific education programs to expand educational access and empower Afghan girls.

Figure 4 Completion and progession rate by gender

EPDC Resources

Among other data sources, unique EPDC data collections for Afghanistan include administrative data from the Central Statistics Office (2001, 2002, 2008-2011), the Ministry of Education (2007), household survey data from MICS (2003, 2011), NRVA (2008), and indicators derived from UIS data.

.PNG)

Add new comment