You are here

Long Path to Achieving Education for All: Highlights from EPDC's latest policy report

Comparing school access and learning outcomes for 20 countries

The following are excerpts from EPDC's latest policy brief, written by Ania Chaluda, Education Policy and Data Center

The last decades have seen an impressive growth in school participation in developing countries. As countries have made remarkable progress towards universal primary school completion, the focus in the development community has shifted to reaching the most disadvantaged populations, and improving the quality of education. Is school access truly universal? And now that most children are in school, do we know whether they are actually learning? EPDC's latest policy brief Long Path to Achieving Education for All: School Access, Retention, and Learning in 20 Countries, the progress that countries have made in schooling access is compared to learning outcomes in order to demonstrate some shortcomings of this progress.

_0.png)

The pyramids presented here were constructed using country-level statistics on school access, survival to a given grade (varies by country) and available data on learning outcomes. The data needed to create each pyramid came from household surveys, international achievement tests, and in a few cases, administrative sources. In short, the pyramids aim to provide a snapshot of a country’s progress in providing universal school entry (access), keeping students in school (survival), and finally, teaching them at least minimum reading skills (learning). The level of access is defined as the difference between 100% and the proportion of 14 year olds who reported never having been to school, and is based on educational attainment as measured in household surveys. The calculation of survival rates, performed by EPDC using a reconstructed cohort method, estimates the percentage of pupils in grade 1 who eventually reach a given grade, regardless of how many times they repeated all preceding grades. This report aligns the survival and learning components of the pyramid for each country by calculating survival to the grade in which a given assessment test was administered. Percentage of pupils who demonstrate at least a low level of learning is used as a measure of learning achievement. In the four tests included in the analysis: PASEC, PIRLS, SACMEQ, and SERCE, this benchmark is defined differently, and the specifics of the definitions used in each of the achievement tests used in this report are explained on page 7 of the report.

In order to determine the final measure used in the pyramids - learning - the percentage of students who reached the basic proficiency as defined by a given achievement test is applied to the percentage of students who eventually transition to the tested grade. Comparing the length of the dark blue bar to the bottom light orange bar representing the entire cohort of children who are of the school entrance age provides a measure of the final inefficiency that the pyramids aim to illustrate: the percentage of 6-year olds who gain basic reading skills by the time they reach a given grade and the percentage of them who do not obtain such reading abilities due to either never entering school, dropping out early or scoring low on the test despite having attended at least several grades of primary schooling. It must be noted that the pyramids are not comparable across all countries. To facilitate comparisons across countries, the pyramids are grouped according to the test that was used to determine the reading abilities.

The dark orange bar representing access is close to 100% in most of the pyramids. The difference between the dark orange bar (access) and light blue bar (survival) shows how many children drop out of school before reaching a certain grade (4, 5 or 6, selected to match the grade in which students reading abilities were tested). In three of 10 countries participating in SACMEQ- Swaziland, Tanzania and Kenya - over 90% of grade 6 students demonstrated basic reading abilities, as defined by the test. Access to school is high: between 93% (Mozambique) and 99% (Swaziland, Zimbabwe) of children enter school. School survival is more of a challenge, especially in Lesotho, Malawi and Mozambique, where about a third of children enrolled in school never make it to grade 6. The same countries were in the bottom four in terms of their performance on SACMEQ suggesting that both survival and learning are major challenges for their educational systems. A country with the lowest score, Zambia, demonstrates high survival (about 90%), but low learning, as merely a half of children are expected to gain basic reading skills by the time they reach grade 6.

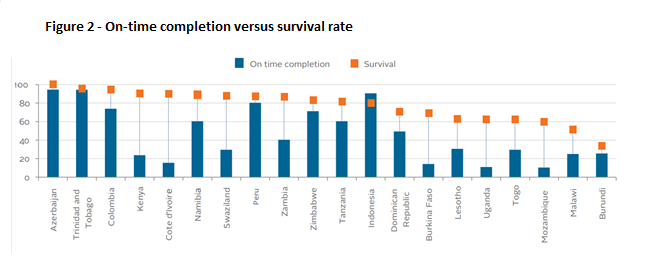

To examine the extent to which high repetition rates are a major challenge in the education systems of the countries analyzed in the study, survival rates to the last grade of primary for the 20 countries were compared to on-time completion. The figure below demonstrates the results of the comparison. Countries are sorted by the difference between survival and completion, represented by a light blue line connecting blue bars (on time completion) and orange squares (survival). As demonstrated in this figure, high repetition is a major challenge in about a half of the countries described in this report. In Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, and Swaziland the difference between on time completion and survival rates is the largest, suggesting that children either enroll much later than they should or repeat multiple times before they reach the last grade of primary school. In these countries, survival rates in primary school are about 90%, but only 16% (Cote d’Ivoire) to 30% (Swaziland) of children who are two years older than the official age of the final grade of primary have completed primary school. In Azerbaijan and Trinidad and Tobago, on the other hand, over 95% of children reach the last grade of primary, most of whom appear to be close to the official age of students in that grade. Nonetheless, a small difference between survival and on time completion is not always a sign of a properly functioning school system. In Burundi survival is about 8% higher than completion - one of the smallest differences across all countries; however, both completion and survival are quite low. This suggests that instead of high repetition, Burundi’s education system can be characterized by very high dropout rates, i.e. children who enroll are likely to leave school before reaching upper primary grades and gaining basic reading skills. The comparison between survival and on time completion demonstrates that behind high survival rates are sometimes hidden very high repetition rates, and suggests that many children struggle to master educational content in primary school. Having an opportunity to repeat a grade instead of leaving school is, however, a much preferred scenario for a struggling student whose chance of eventually reaching basic reading abilities is much higher in school than outside of it.

Add new comment