You are here

Violence Threatens Educational Gains in Central America

Gang violence is threatening children's safety and well being throughout Central America. It is also threatening the impressive educational gains many nations have made over the past two decades.

Over the past few months, the United States has been caught off guard by the thousands of unaccompanied minors entering the country across the Mexican border. Projections estimate that in 2014, more than 90,000 unaccompanied children will enter the United States, up from 16,056 in 2011. The vast majority of these children are from three countries in Central America – Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala.

What is remarkable is how young many of the Central American children are: of the unaccompanied minors apprehended in the United States thus far in 2014, more than 27% of Hondurans, 22% of El Salvadorians and 10% of Guatemalans were under the age of 12. In contrast, only 3% of Mexican migrants were younger than 12. Widespread gang violence and poverty were cited as the reason most of the children have been sent by their families to the United States. Weak and corrupt central governments have been unable to enforce the rule of law, allowing gangs and militias to control large swaths of Central America through coercion and violence.

Thriving Education Systems

Given this mass exodus of children from Central America, it would be easy to assume that these three nations have simply failed their children. In fact, that is simply not the case. It may seem surprising, but the formal educational systems in all three nations have been thriving – Central American nations have emerged from the devastating civil wars and economic crises of the 1980s admirably dedicated to expanding educational opportunities to all children.

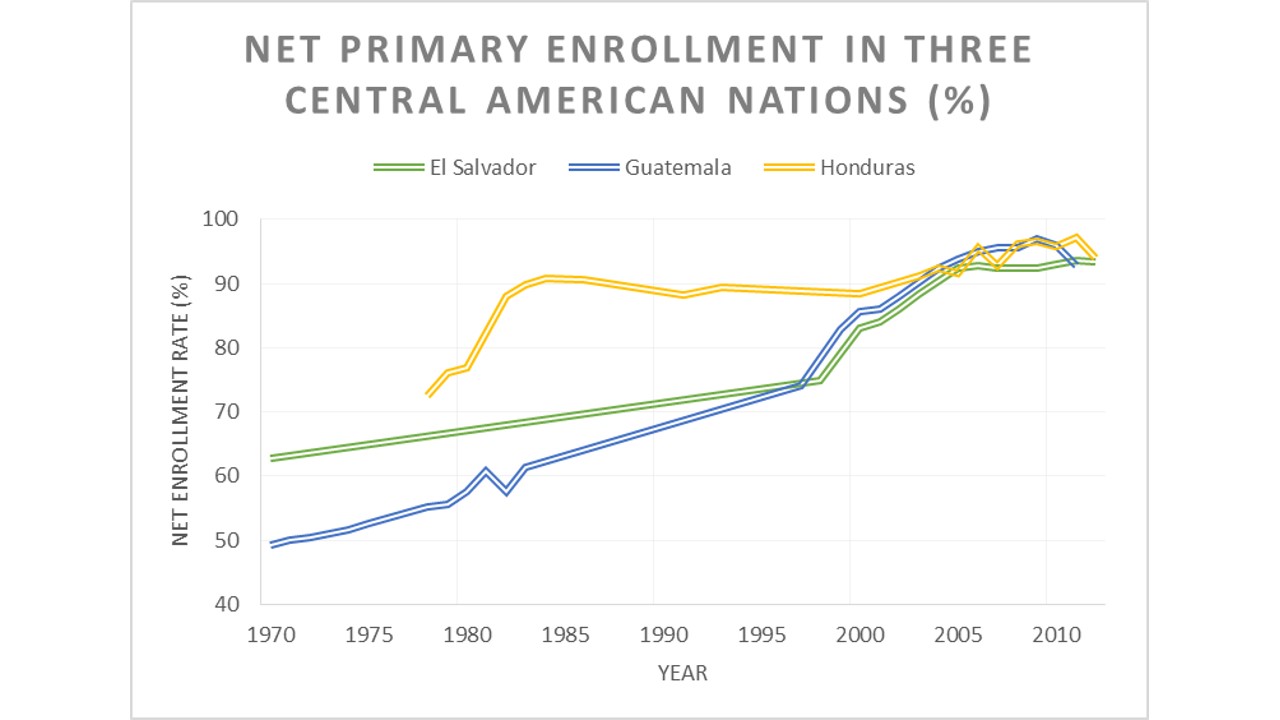

The graph below shows the net enrollment rate (NER) in primary school for Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador between 1970 and 2012. It is clear that during their civil wars, both Guatemala and El Salvador had low levels of primary schooling, and were hardly able to expand access to primary schooling. Honduras, meanwhile, made significant improvements in expanding primary enrollments as early as the 1980s.

Despite low initial levels of primary enrollment, access to primary school has increased rapidly since the mid-1990s in both El Salvador and Guatemala, just as the two nations were emerging from devastating civil wars and transitioning towards democratic rule. Today, the NER stands at roughly 93% in all three countries, up from less than 75% in the mid-1990s – suggesting that all three nations are close to meeting their Education for All (EFA) commitments.

(Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Data interpolated for missing years)

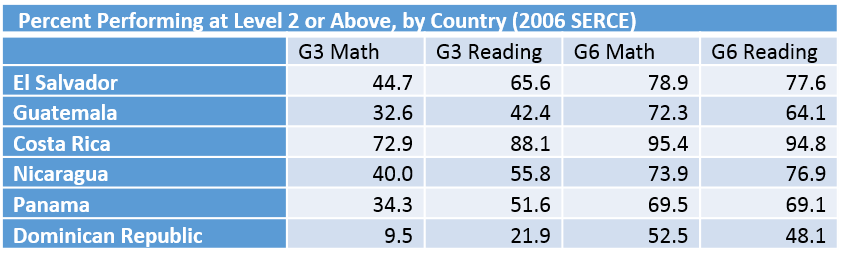

Additionally, despite valid concerns over the quality of education in these three nations, El Salvador and Guatemala are certainly no worse than their Central American peers in terms of educating students (data on Honduras not available). The table below show the percent of students who achieved Level 2 in Math and Reading in Grades 3 and 6, respectively. The data are drawn from EPDC extractions of the Second Comparative Regional Exam (Segundo Estudio Regional Comparativo y Explicativo), a regional assessment conducted throughout Latin America in 2006. In 3rd grade, Level 2 corresponds to the ability to locate information in a brief text and to perform addition and multiplication problems. In 6th grade, Level 2 corresponds to being able to distinguish information in the middle of texts from those in other parts and to identify and complete sequences or solve addition problems using fractions and decimals.

The data suggest that in terms of student learning outcomes, El Salvador and Guatemala are roughly in the middle of the pack of Central American nations in terms of their ability to ensure their children meet basic learning outcomes. For example, 44.7% of third graders in El Salvador meet Level 2 benchmarks in Math and 65.5% do in reading. Although not as high as the percentages in Costa Rica (72.9% and 88.1%, respectively), El Salvador is doing better than Nicaragua, Panama and substantially better than the Dominican Republic at 9.5% and 21.9%

Protecting Children’s Right to Education

Despite these nations’ huge gains in educational access, gang violence is threating the safety and wellbeing of children. Anecdotal evidence suggests that students are already dropping out of school at higher rates than only a few years ago, largely due to security concerns in their communities. Perhaps even more concerning is the fact that schools themselves are sometimes used for recruitment into gangs.

It is clear that education cannot solve the problem of gang violence in Central America - gang violence has thrived even while educational development has succeeded. Since the mid-1990s, the development community has supported massive expansion and reform of educational systems throughout the region. Now, it must call for central governments to re-establish order and rule of law or else watch the gains these nations have made slowly reverse.

More broadly, Central America nations have important lessons to share about what education can and cannot accomplish in post-conflict settings. The important take away is that merely providing access to education is not enough to protect children’s right to education. In addition to access, schools in post-conflict settings must establish strong links to the local community in order to ensure that schools become safe havens for students. At the curricular level, citizenship education must teach the principles of democratic participation, as post-conflict nations transition from authoritarian rule. Similarly, education without economic opportunities leaves children with few opportunities for finding employment – making them particularly vulnerable to participation in gangs. Educational interventions must continue to be linked to skills training that helps children transition to productive employment.

Add new comment